by Loghan Hawkes

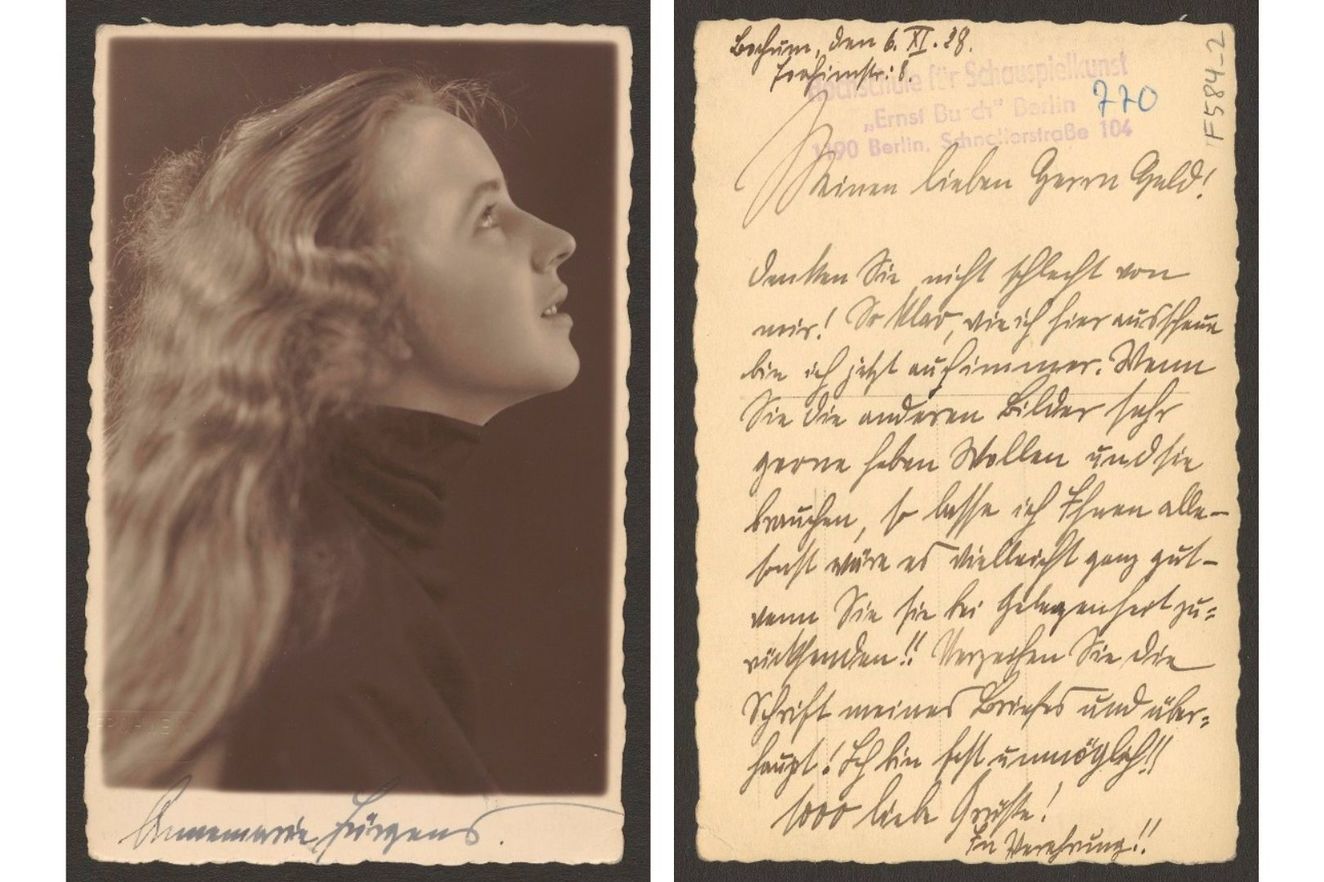

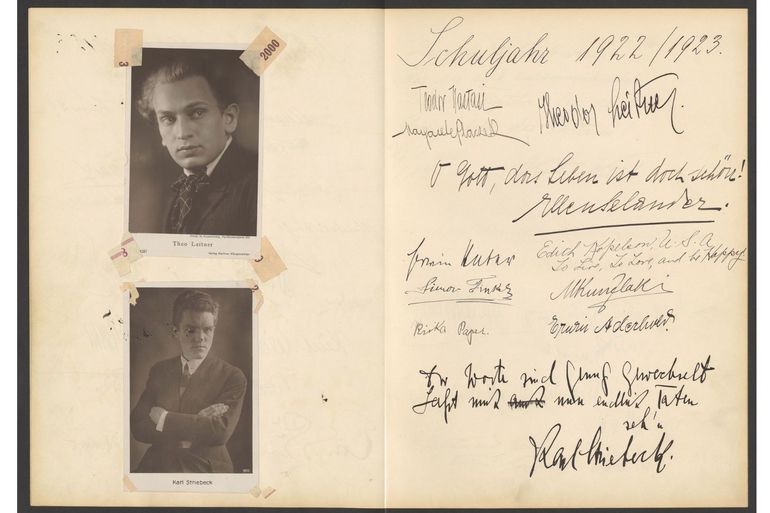

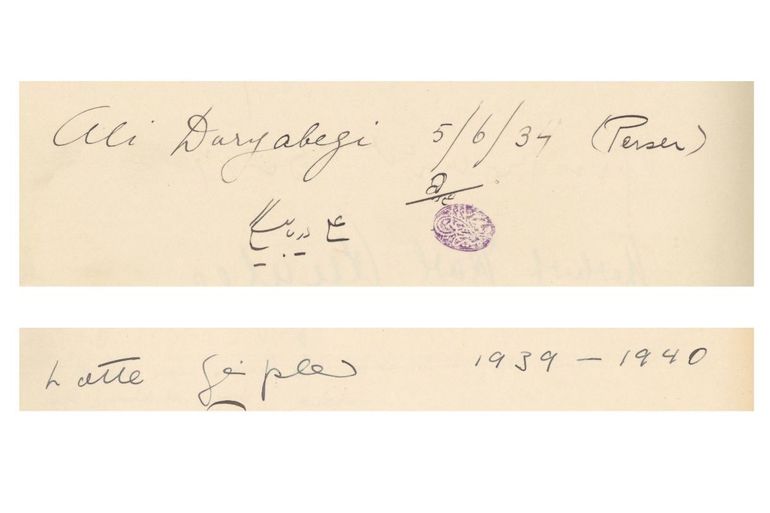

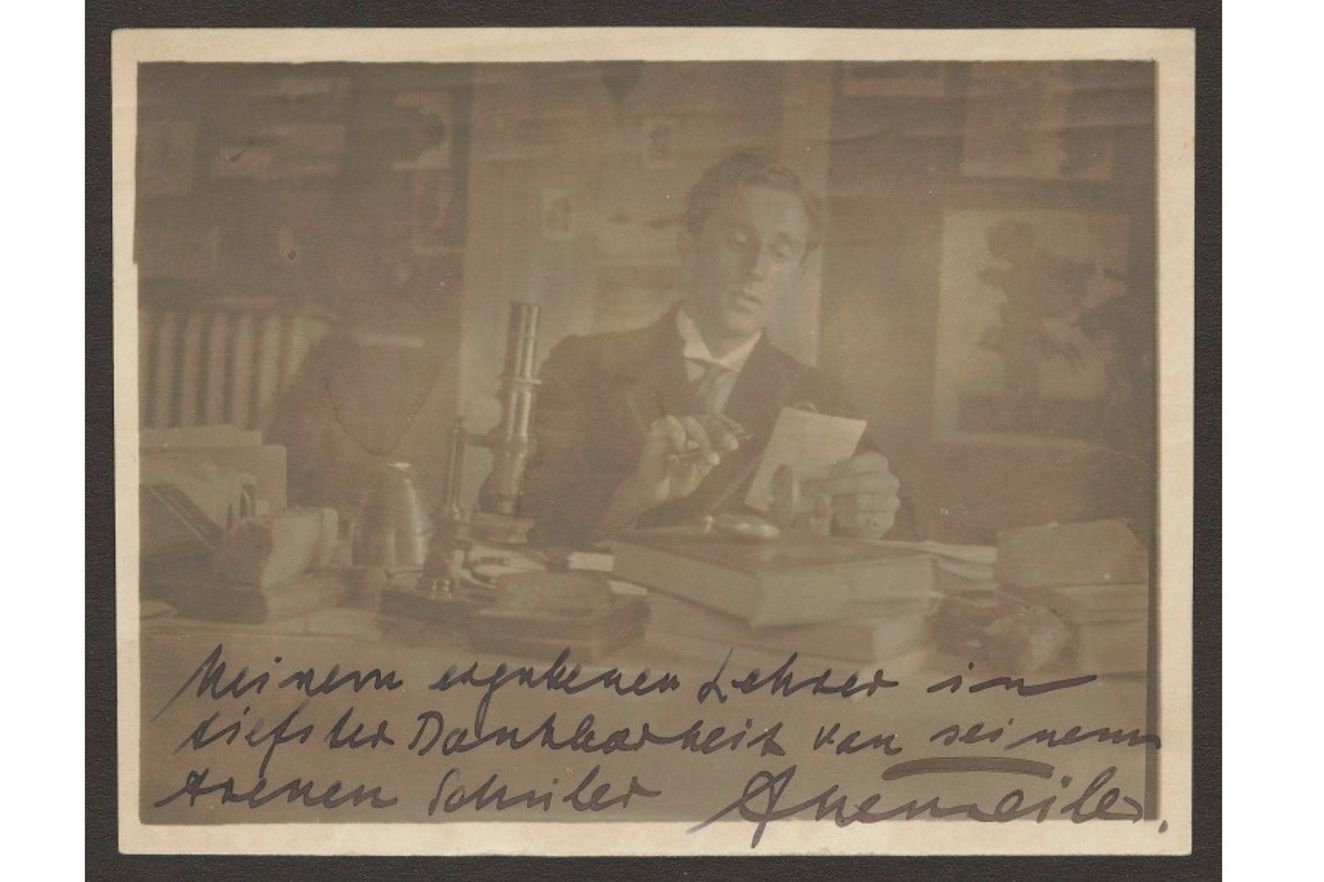

The latest project from the Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch archive makes a collection of photographs and written materials from the years when the acting school was connected to the Deutsches Theater (1905 to 1951) available for public research. These primary sources offer a unique perspective of German theater history before, during, and after the world wars.

Although HfS Ernst Busch has only existed as a university since 1981, the school's history dates back to the early 20th century. In October 1905, well-known theater director Max Reinhardt opened an acting school for the Deutsches Theater, which had become part of his theater company earlier that year. At the time, Reinhardt's network consisted of eleven Berlin theaters; this only changed upon the seizure and subsequent dissolution of the company by National Socialists in 1933. However, the drama school made it through the following years of dictatorship, war, and aftermath, until it was renamed in 1951, becoming the Staatliche Schauspielschule Berlin under the government of the GDR. Another thirty years passed before the school was granted official university status along with its current name, which pays tribute to belovéd East German actor Ernst Busch. While each period of the school’s history has its own unique reasons for intrigue, it is in the earliest era that this article takes primary interest, from the school’s creation through its establishment as a respected educational institution in the German theater world.

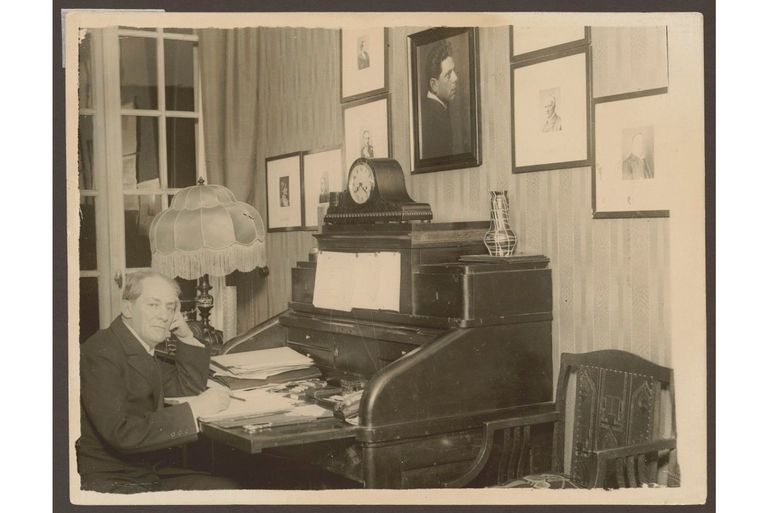

Max Reinhardt’s acting school, which became known as the Schauspielschule des Deutschen Theaters zu Berlin, saw its headmaster in one Berthold Held, a friend of Reinhardt’s who was dedicated to the education of young theater artists, and whom students continually wrote to even decades after he first took the job. Held cared deeply about the school until the very last, remaining in his position until he took ill in 1931. Five months later in his final letter to Reinhardt, he articulated his worries about the longevity of the school, which faced financial threats that were exacerbated in his absence. Although he did not live to see it, he would be glad to know that his fears were never realized; not only did the school persist, but its history did as well. Each photo, signature, and written sentiment found in our archive is connected to people without whom this school would not be what it is today. It is our job and the aim of this project to not only bring these records back to life, but to keep them alive by making them accessible to the public.